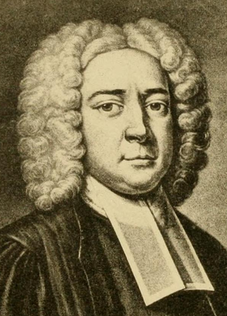

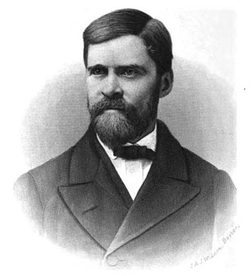

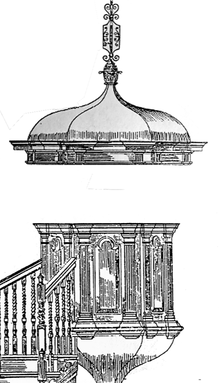

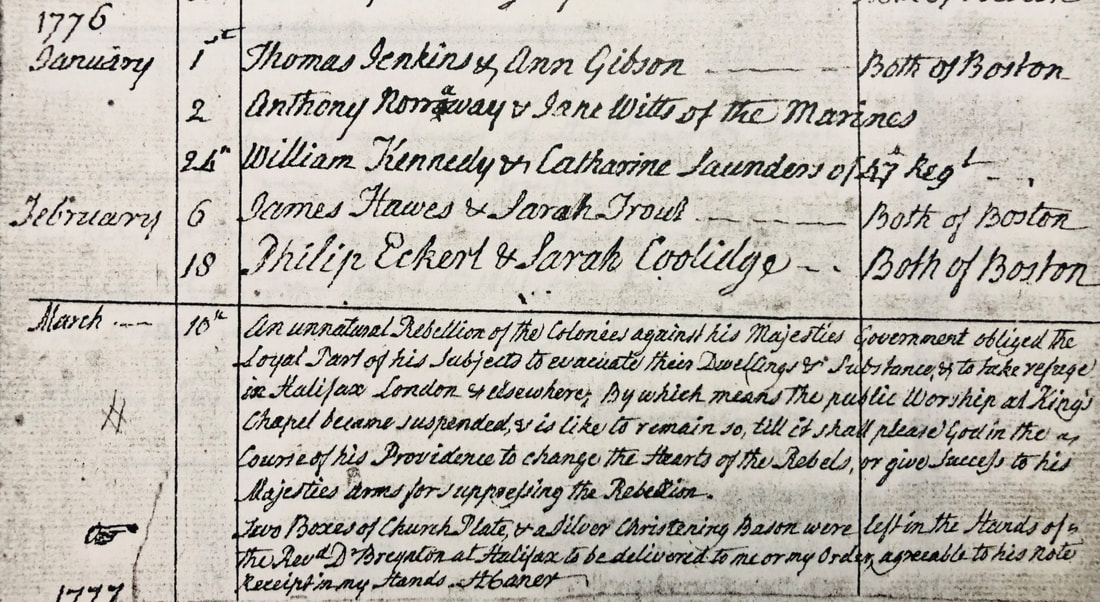

By William StilwellHistoric Site Educator  Each year in Boston, March 17 not only marks St. Patrick’s Day, but also Evacuation Day: the anniversary of the 1776 day when British troops evacuated Boston, marking the end of the Siege of Boston during the American Revolution. Historic Site Educator William Stilwell explores the impact of Evacuation Day on King’s Chapel as a faith community and how its ministers reflected on that period in the church’s history. “Continue...thy favour to our sovereign lord King George, and all that are employed under him...Let no unhappy divisions disquiet his reign, or interrupt the internal harmony of his government.”  The Reverend Henry Caner The Reverend Henry Caner The Reverend Henry Caner spoke these words as part of a short prayer before his sermon, “The Great Blessing of Stable Times”, on August 11, 1763 at King’s Chapel to celebrate the end of the French and Indian War. Despite his optimistic words, thirteen years later in March of 1776 he would flee Boston without much more than the clothes on his back, leaving behind his congregation of nearly thirty years, never to return. As the King’s troops evacuated Boston, Caner and almost every other civilian loyal to the crown, including some from his own congregation, faced the gut-wrenching decision to disrupt their lives and abandon their homes as the Continental Army besieged Boston.  The Reverend Henry Wilder Foote The Reverend Henry Wilder Foote One hundred years later, in March of 1876, King’s Chapel minister the Reverend Henry Wilder Foote gave a sermon in part to commemorate the centennial of Evacuation Day. In a year of celebrating patriotism, in a country and city that valued and still values its revolutionary pedigree above all else, Foote took a markedly different approach. Instead of glorifying Boston’s liberation and highlighting the members of the so-called patriots of the congregation, Foote instead focused on the other side of the story: the Loyalists, the Tories, the Friends of Government, those who “paid the bitter price of exile and ruin.”  King's Chapel 1717 pulpit and sounding board King's Chapel 1717 pulpit and sounding board He starts with Reverend Caner, preaching up from the 1717 pulpit that still stands in the chapel today, and then looks down and goes pew by pew, starting with pew 4, Charles Paxton. Paxton had been in charge of customs for years in Boston, earning him the ire of many of his neighbors and maybe even a few of his fellow parishioners. In 1767, at the height of the crisis over the Townshend Acts, Pope’s Night celebrations in Boston saw Paxton hanged in effigy along with the Pope and the Devil, labeled with the extremely harsh caption “every man’s ser-vant, but no man’s friend.” Behind him, in pews 7 and 8, Foote covers the family of Dr. Sylvester Gardiner, for many years the Senior Warden and a prominent physician who Foote says left behind his “valuable stock of medicines and drugs for Washington’s army.” Here Foote leaves out Gardiner’s status as an enslaver. Further up the center aisle in pew 10, Foote mentions Isaac Royall Jr. and his “noble Medford farm,” leaving out the detail that next to Royall’s beautiful Georgian estate stands an out building where the Royall’s enslaved dozens of African men, women, and children. Foote then moves over to the right side aisle, highlighting the Governor’s Pew, built for Royal Governor William Shirley, where Governors and other dignitaries would have sat, the true epitome of royal authority in Massachusetts. During the months of the siege many of the soldiers occupying the town may also have been seen among the pews. Foote only mentions the male evacuees among the congregation, but when revisiting this moment in his larger history of King’s Chapel, the Annals, he mentions the two women sitting behind the Governor’s pew in pew 36, sisters Elizabeth and Ame Cuming. These single women ran their own business together among a community of female entrepreneurs known then as “she-merchants.” They would find themselves opposed to the rebellious side in Boston because of their importation of boycotted goods and as a result would be among those who evacuated on March 17th. Rather than recounting the story of evacuation on March 17th, Foote instead imagines the last Anglican service held at King’s Chapel before evacuation, as the congregation returned after the war to emerge as North America’s first Unitarian church. Foote takes his 19th century congregation on a tour of the 18th century congregation, introducing them to each of the parishioners who may have attended that last service and never returned. This was by no means the entire congregation- far from it, only about a third could be considered loyal to the crown. But Foote wanted to give those individuals their due. In doing so, he paints a rosy picture, very notably omitting the ties to slavery many of these congregants had. On his last day, after being abruptly informed that troops were leaving and that he too would have to leave, Reverend Henry Caner gathered up his “bedding, wearing apparel, and a little provision” as well as the church’s communion silver and register of baptisms, marriages, and burials. In the King’s Chapel Register of Marriages, Caner recorded his last entry: “An unnatural Rebellion of the Colonies against his Majesties Government obliged the Loyal Part of his subjects to evacuate their Dwellings...public Worship at King's Chapel became suspended and is likely to remain so till it shall please God... to change the hearts of the Rebels or give Success to his Majesties arms.” Caner never returned to Boston, and the congregation would not resume service at King’s Chapel until 1782. The remaining congregation would eventually resume service without him, beginning its new life as an independent chapel in an independent country. Sources: Caner, Henry. “The Great Blessing of Stable Times,” August 11, 1763. “Cuming Sisters:‘She-Merchants’ of Boston.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/cuming-sisters.htm. Foote, Henry Wilder. Annals of King’s Chapel: From the Puritan Age of New England to the Present Day. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1896. Foote, Henry Wilder. KINGS CHAPEL AND THE EVACUATION OF BOSTON: a Discourse. Boston, MA: George H. Elis, 1876. King's Chapel (Boston, Mass.) records, Massachusetts Historical Society. Newton, Ross. Patrons, Politics, and Pews: Boston Anglicans and the Shaping of the Anglo-Atlantic 1686-1805. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Register of Marriages at King’s Chapel, Boston. Massachusetts Historical Society.

2 Comments

3/19/2020 08:56:30 am

Thanks Will- you should do more writing! How about a piece on KC and the Alcott Family, or Dr. Joseph Warren or Joseph Warren Revere and Family?

Reply

Molly Caner

1/12/2022 12:20:30 pm

Hi there,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed