KING'S CHAPEL

-

Explore Sources

-

Biography

-

Reflection

<

>

Below are two King’s Chapel records relating to a woman and her family. As you scan these documents, consider how these sources compare and differ with other vital register pages in this exhibit.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

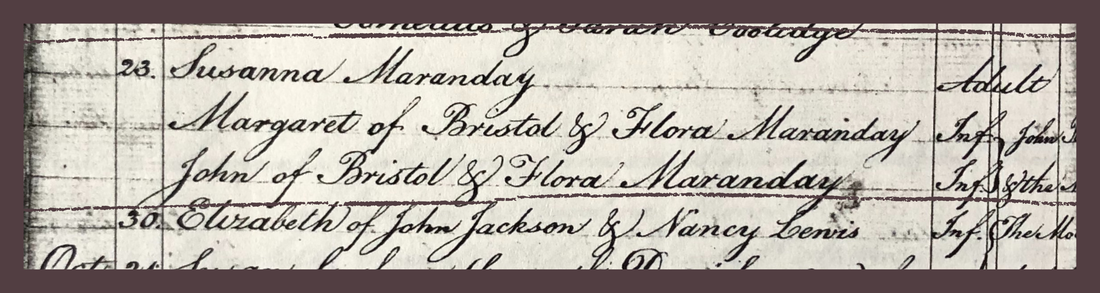

The first document shows baptisms - or christenings - held at King’s Chapel between August and November 1804. About halfway down the page are the baptisms of three members of the Maranday family: Susanna, Margaret, and John. While Susanna is identified as an adult, her younger siblings are both identified as infants, or young children, at the time. Their parents - Bristol and Flora Maranday - served as baptismal sponsors for the children, alongside a John Richardson. The family is not identified explicitly as being Black in this document, as seen so many times before. Yet, the mother’s race is described in a second document, the record for Flora Maranday’s burial service at King’s Chapel on March 24, 1815. The entry reads “Flora Maranday...Black...48 years.” No mention of her family is made here, but further research reveals more of her family’s story. In the case of researching the Maranday family, Flora’s burial register was found prior to the record of baptisms. Knowing a bit about Flora Maranday enabled us to connect this family history together when the second record was found.

The dates and names of the Maranday family in church records enabled us to locate further information about Flora and her family in archives outside of King’s Chapel. Her will and probate records, available online through the New England Historic Genealogical Society, widened the window through which researchers can look at her life.

The probate papers were recorded under the name “Flora Miranda,” but the information in the documents reveals this to be the same women and family. She had previously been widowed by her husband “Bristow Miranda,” which refers to the “Bristol Maranday” who was still alive at the time of their children’s baptism in 1804. Additionally, her children Susanna, Margaret, and John are each mentioned in the probate papers.

In a letter dated June 1, 1815, Flora’s daughter Susanna Marandy wrote to probate judge James Prescott requesting that Primus Hall be appointed as the administrator of Flora’s will, explaining that two of Flora’s children, John and Margaret were still minors. “Primus Hall of said Boston, soap boiler,” as Susanna described him, was the son of famed Boston Black leader Prince Hall.

The paperwork notes that Flora was a widow, that she died of an illness, and lists her place of residence as Charlestown. At the time of her death, Flora owned “part of a house consisting of one lower room and the cellar under it, and a lot of land adjoining the same of about fourteen square nods.” Flora’s possessions -- including her home, a tin candle box, iron kettle, four chairs, an old feather bed, and a looking glass -- were valued at just over $251.88, roughly $4,050 in today’s buying power.

Unfortunately for the executor of her estate and her family, the costs of her funeral, debts, and fees paid for the inventory of her estate exceeded the value of her estate by $32.88. While most of her real estate and household possessions were sold by Primus Hall at auction, the fate of her children is not included in the records. That said, it is likely that John and Margaret would have been taken in by their older sister Susanna.

The probate papers were recorded under the name “Flora Miranda,” but the information in the documents reveals this to be the same women and family. She had previously been widowed by her husband “Bristow Miranda,” which refers to the “Bristol Maranday” who was still alive at the time of their children’s baptism in 1804. Additionally, her children Susanna, Margaret, and John are each mentioned in the probate papers.

In a letter dated June 1, 1815, Flora’s daughter Susanna Marandy wrote to probate judge James Prescott requesting that Primus Hall be appointed as the administrator of Flora’s will, explaining that two of Flora’s children, John and Margaret were still minors. “Primus Hall of said Boston, soap boiler,” as Susanna described him, was the son of famed Boston Black leader Prince Hall.

The paperwork notes that Flora was a widow, that she died of an illness, and lists her place of residence as Charlestown. At the time of her death, Flora owned “part of a house consisting of one lower room and the cellar under it, and a lot of land adjoining the same of about fourteen square nods.” Flora’s possessions -- including her home, a tin candle box, iron kettle, four chairs, an old feather bed, and a looking glass -- were valued at just over $251.88, roughly $4,050 in today’s buying power.

Unfortunately for the executor of her estate and her family, the costs of her funeral, debts, and fees paid for the inventory of her estate exceeded the value of her estate by $32.88. While most of her real estate and household possessions were sold by Primus Hall at auction, the fate of her children is not included in the records. That said, it is likely that John and Margaret would have been taken in by their older sister Susanna.

Flora Maranday and her family prove a strong example of how fairly-detailed church records are able to let researchers piece together a family history, bringing a family and their struggles into light for the first time in centuries. Without knowing the names and relations of each family member through the church records, it may not have been possible to confirm that the probate records for Flora Miranda were in fact those of Flora Maranday. Without standardized spellings or computer databases in the early 19th century, it can often be difficult to confirm identities of people. This can be an added challenge when conducting genealogical research for Black families in the 18th and early 19th century United States, especially when many enslaved Black people only appeared in sources relating to the people who enslaved them and without surnames. With further research, historians may be able to learn more about the Maranday family through John, Margaret, and Susanna.

www.kings-chapel.org | 58 Tremont St. Boston, MA 02108 | 617-227-2155