KING'S CHAPEL

-

Explore Sources

-

Biography

-

Reflection

<

>

Based on your experience studying the previous document, what do you notice here?

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

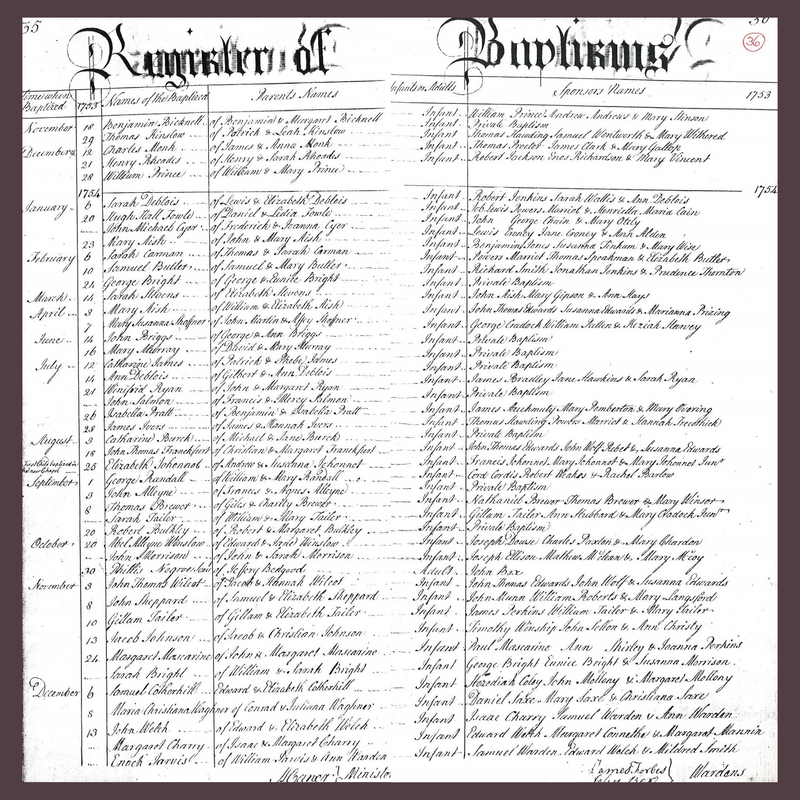

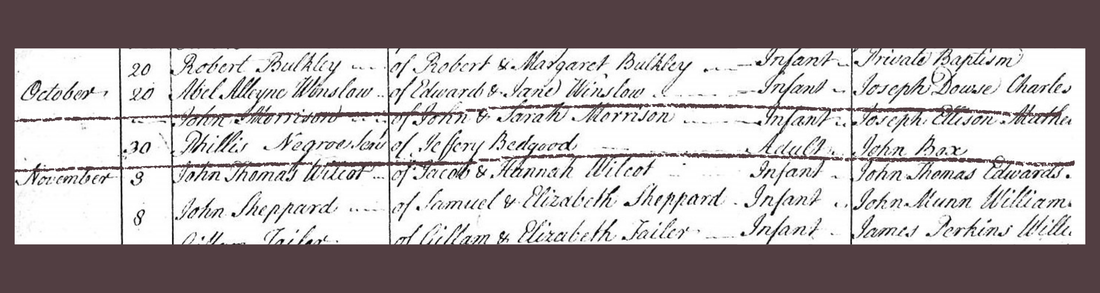

Much like Richard’s baptism, Phillis’s baptism at King’s Chapel stands out from others on the page. “Phillis, Negroe Serv. of Jeffry Bedgood,” baptized at King’s Chapel on October 30, 1754. As with Richard, we see that Phillis is listed as an adult, and Jeffry Bedgood enslaved her at the time of her baptism. Looking at a few entries above Phillis’s name, a note in the left margin shares that August 25, 1754 marked the first baptism in the new chapel, completed in stone in August 1754. It can then be inferred that Phillis was the first Black person baptized in the stone chapel, as unlike Phillis the children listed above her were not accompanied with a racial signifier. Additionally, though Bedgood was not a member of King’s Chapel, the record lists a baptismal sponsor, a church member named John Box.

|

While Phillis first appears in the same source of records at King’s Chapel as Richard, more details of her life have been uncovered through further research. Because Black women in colonial New England, especially those enslaved, tended to not know how to read or write, researchers are forced to depend on writings from white men of some social standing to learn more about enslaved people. Knowing that Phillis was an adult woman living in Boston in 1754 and was enslaved by a man named Jeffrey Bedgood, we can attempt to learn more about her life through looking at primary sources related to Bedgood. An excellent source of information that often results in information about enslaved individuals in Boston are will and probate records of known enslavers. A probate inventory is an evaluation of someone’s personal property and real estate holdings at the time of their death, and since enslaved individuals were legally considered property in 18th century Boston, the names of people enslaved at the time of the enslaver’s death often appear in these records. In the case of Phillis, she is also discussed in Bedgood’s will.

In his 1758 will, Bedgood set specific instructions in his will regarding Phillis's life after his death: |

"I give unto my Negro Woman Fillis her Freedom, & do hereby immediately offer my decease, discharge, & sett her at Liberty, from all & every Person, & Persons whatsover - And I do hereby enjoin my Nephew Jeffrey Williams to procure & give such Security as by Law is require in the Manumission of Negroes before my Executor pays him."

In this entry, to ensure that his wishes were carried out, Bedgood added the stipulation that his nephew would not receive his inheritance until he ensured Phillis's freedom. We know from Bedgood’s funeral expenses that before securing her freedom, Phillis attended Jeffrey Bedgood's funeral, but not by choice - the family still enslaved her until they settled Bedgood's estate. The funeral expenses included "making gown for Negro Woman & Shoes," indicating that Phillis wore a new outfit to what was hopefully her last obligation as an enslaved woman.

Unfortunately at this time, this is all we know about Phillis, as the archival resources dry up after the death of the man who enslaved her. This is again an issue researchers often come up against when researching enslaved people during this era. Given the marginalized status of Black women like Phillis during the mid-18th century, and low literacy rates among enslaved and free Black people in Boston, often the only records we are able to locate are from the perspective of white oppressors. Ironically, racist language in archival records can aid researchers in their ability to dig into the histories of women like Phillis.

www.kings-chapel.org | 58 Tremont St. Boston, MA 02108 | 617-227-2155