KING'S CHAPEL

-

Explore Sources

-

Biography

-

Reflection

<

>

The documents below are displayed in chronological order, though each appears in a different vital register kept by King’s Chapel. In cross-referencing each of these pages, major moments in one man’s life begin to come into focus. Look closely to determine what each page below is. Are you able to locate any similarities across each document?

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

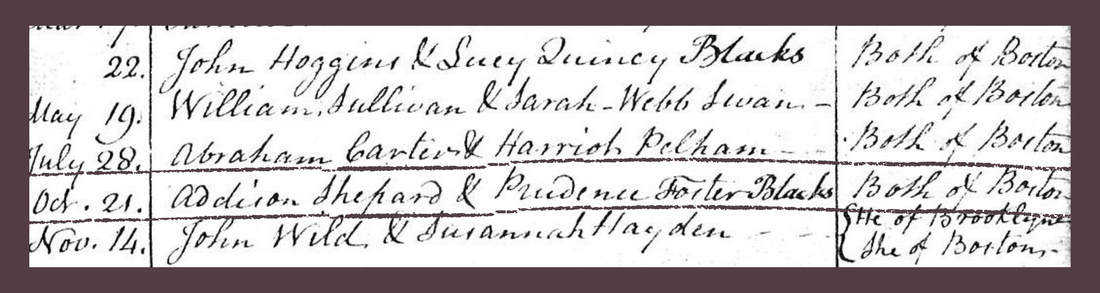

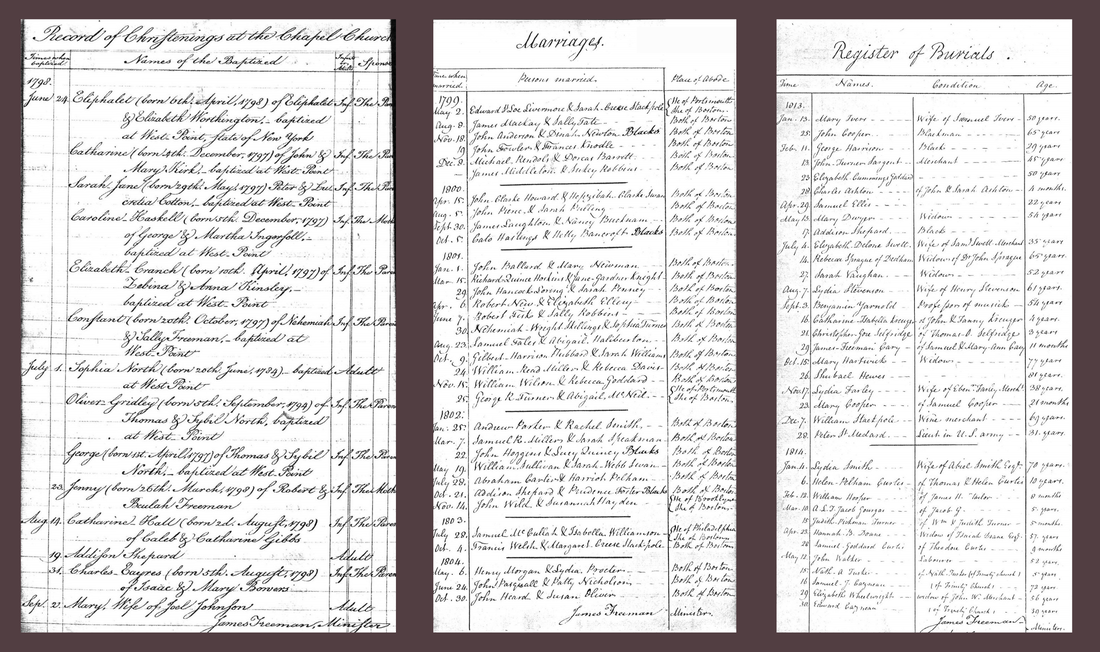

In order, these sources illustrate major moments in the life (and death) of Addison Shepard over a span of 15 years. Shepard first appears in King’s Chapel records on August 19, 1798 when he was baptized as an adult. Four years later, Shepard is again seen at King’s Chapel -- this time for his marriage to Prudence Foster on October 21, 1802. When he died in 1813, Shepard’s burial service was held at King’s Chapel.

Although currently we only are aware of the above church records related to Addison Shepard’s life, they reveal his sustained relationship with King’s Chapel. By researching Shepard across these three different church registers, we learn that he is the only Black person of whom we are aware at this time who was baptized, married, and buried by King’s Chapel. Prudence Foster only appears explicitly at King’s Chapel at the time of her marriage. If Addison Shepard and Prudence Foster had any children, they were not baptized at King’s Chapel. That said, the couple served as baptismal sponsors for the child of another couple. On September 30, 1804, Addison and Prudence were present for the baptism of Elizabeth, a young daughter of John Jackson and Nancy Lewis. Without further information available at this time, we can only speculate about the nature of the relationship between the two families.

Sometimes the only sources known for Black individuals during this time period are church vital records, like these which share details of Shepard and Foster’s lives. The frequent scarcity of other textual records underscores how important church records can be in uncovering their stories through text. This example also shows the significance of carefully making note of the dates records were made. Unlike other people discussed in this exhibit such as Richard and Phillis, Addison Shepard’s connections with King’s Chapel were likely intentional. While enslaved people in the 18th century were often forced into baptism at predominantly white churches like King’s Chapel by their enslavers, after abolition in Massachusetts in 1783, we see people like Shepard forging their own relationships with religious institutions on their own terms, particularly during this time before Boston’s first African American congregation acquired its own building in 1806, the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill (now a museum).

www.kings-chapel.org | 58 Tremont St. Boston, MA 02108 | 617-227-2155