KING'S CHAPEL

-

Explore Sources

-

Biography

-

Reflection

<

>

As we saw with the Hill family, church vital records often form a strong basis for learning about families and relationships within the church, particularly at a time when full membership in the church was limited to wealthy, white men. These documents share two important dates in the life of one Black man who worshipped at King’s Chapel. Are you able to locate this individual? What information can be learned about this couple from these two sources? Where might we turn for further information?

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

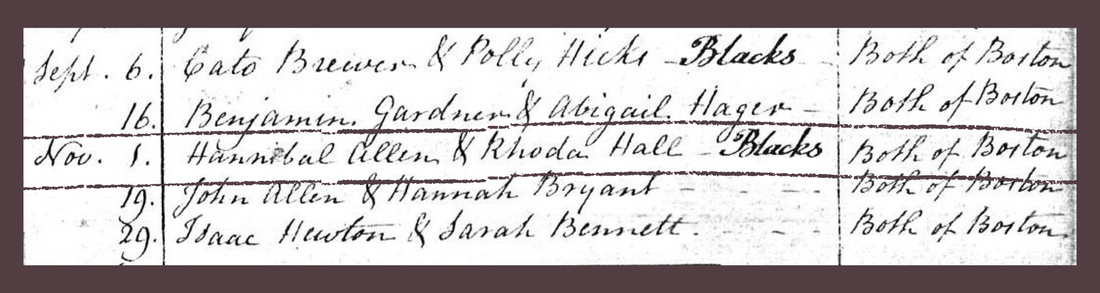

From these materials, we learn of the marriage of Hannibal Allen and Rhoda Hall, a couple living in Boston at the end of the 18th century. Allen and Hall were married at King’s Chapel on November 1, 1795. Unlike with the Hill family, we have been unable to locate any baptismal records of children Allen and Hall may have had. Unfortunately, we do learn that Hannibal Allen died young, passing away in August of 1800 at age 38. While Hannibal Allen was not baptized at King’s Chapel, we are able to estimate the year he was born - 1762 - and his age when he married - 33 - based on the information provided in the register when he was buried. Because we have recorded surnames for Rhoda Hall and Hannibal Allen, the chance of locating additional information about them increases. What details can we uncover about the couple? What of Rhoda’s life after her husband’s death?

The heavy penmanship reading “Blacks” after the names of five of the couples married by Reverend James Freeman at King’s Chapel between 1793 and 1796 is a stark and painful reminder of the enduring racism within not only the church, but the United States, following American Independence from Britain, and the failure to deliver on the promises of revolutionary ideals for freedom and equality for all in the United States.

The heavy penmanship reading “Blacks” after the names of five of the couples married by Reverend James Freeman at King’s Chapel between 1793 and 1796 is a stark and painful reminder of the enduring racism within not only the church, but the United States, following American Independence from Britain, and the failure to deliver on the promises of revolutionary ideals for freedom and equality for all in the United States.

Further research has helped identify several other sources relating to Hannibal Allen and Rhoda Hall, helping to flesh out what their lives were like in Boston around the turn of the 19th century. These include a booklet produced by a fraternal organization to which Hannibal Allen belonged, tax information, and will and probate records produced around the time of Allen’s death.

A tax document from 1800 discloses additional details about Allen’s life. At the time this document was created, Allen owned a small house on May Street, now called Revere Street on Boston’s Beacon Hill. His occupation while living here is listed as a labourer. This document places Hannibal Allen and Rhoda Hall as residents of Beacon Hill’s north slope, a historically free, Black neighborhood in Boston, which was a center of abolitionist activity in the city in the early 19th century.

Even in death, primary sources can shed light on someone’s life - both the deceased and the people they left behind. After Hannibal Allen died, an inventory of his personal property sheds light on smaller details of his life. In his home, Allen had modest possessions: furniture, bedding, “crockery ware,” tinware, a lot of iron ware, mirrors, and various sundries. His estate was valued at $516.70, including his house. A document accompanying Allen’s probate inventory shares more information about Rhoda Hall after her husband’s death. By 1804, we learn that “Rhoda Allen, widow [of Hannibal Allen]” has remarried a man named Julius Angel. Angel accompanied her to the final settling of her first husband’s estate. While Rhoda Allen provided a mark (indicating she likely could not read or write), her second husband signed the document in his own hand.

A tax document from 1800 discloses additional details about Allen’s life. At the time this document was created, Allen owned a small house on May Street, now called Revere Street on Boston’s Beacon Hill. His occupation while living here is listed as a labourer. This document places Hannibal Allen and Rhoda Hall as residents of Beacon Hill’s north slope, a historically free, Black neighborhood in Boston, which was a center of abolitionist activity in the city in the early 19th century.

Even in death, primary sources can shed light on someone’s life - both the deceased and the people they left behind. After Hannibal Allen died, an inventory of his personal property sheds light on smaller details of his life. In his home, Allen had modest possessions: furniture, bedding, “crockery ware,” tinware, a lot of iron ware, mirrors, and various sundries. His estate was valued at $516.70, including his house. A document accompanying Allen’s probate inventory shares more information about Rhoda Hall after her husband’s death. By 1804, we learn that “Rhoda Allen, widow [of Hannibal Allen]” has remarried a man named Julius Angel. Angel accompanied her to the final settling of her first husband’s estate. While Rhoda Allen provided a mark (indicating she likely could not read or write), her second husband signed the document in his own hand.

Hannibal Allen’s involvement in the African Society opens the possibility of learning more of his life story. From that knowledge, one may begin to trace his social circles, both in and outside of the church. Hannibal Allen was one of 44 charter members of the African Society, a fraternal organization for Black men in Boston, founded in 1796. The final page of the “Laws of the African Society,” in the collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, lists its forty-four charter members, including Hannibal, Cato Morey, and Darby Vassall, whose families also appear in King’s Chapel records around this time. The African Society was “a group of African Americans organized to provide a form of health insurance and funeral benefits, as well as spiritual brotherhood, to its members.” The document outlines membership fees, benefits, and requirements for participation in the society. Much emphasis is placed on helping support families if a member of the society passed away. Rhoda Hall potentially benefited from her husband’s participation in this Society when he died. With at least two known connections between Allen, Vassall, and Morey - through their church and this organization - perhaps these men and their families were friends or acquaintances. Learning more about one of these men could shed light on the lives of the others.

www.kings-chapel.org | 58 Tremont St. Boston, MA 02108 | 617-227-2155