|

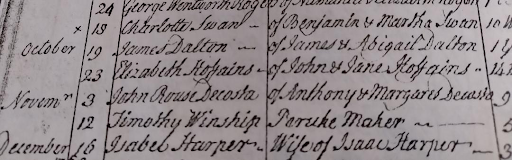

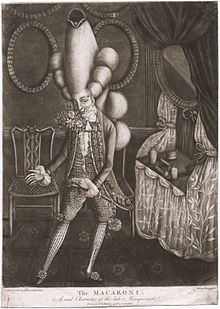

by Lin Nulman, Historic Site Educator When visitors read the History Program’s informative signs in King’s Chapel, they see several portraits of its “bigwigs.” And some have very big wigs indeed, which is the origin of that expression! The history of gentlemen’s wigs from the mid-1600s to the early 1800s appears in the images along the chapel’s center aisle. Wig history is about wealth, elaborate high-fashion, a taste for artificiality in personal style, disease, taxes, and, in Boston, even Revolutionary feeling. Long, curly locks were the ideal for European men in the 1600s. Sources agree this ideal was a problem for King Louis the XIV of France, who began balding as a teenager. When he and King Charles II of England, his prematurely graying cousin, began to wear lush wigs in the mid-1600s, courtiers and the rich were quick to imitate them. Men’s wigs became an important fashion trend. King Charles II by John Michael Wright or studio, 1660s: image from Wikipedia The wigs of that period, and into the early 1700s, were larger than those of the later 1700s. Royal Governor Sir Edmund Andros, who seized a piece of Boston city property in the 1680s for the building of the first King’s Chapel (where the current chapel stands now), wore a typical wig with a huge flow of curls. Royal Governor Sir Edmund Andros by Frederick Stone Batcheller: Image from Wikipedia Wigs (some styles were called perukes or periwigs) were made of human, horse, or goat hair. White hair was desirable but rare, so powder allowed men to get the white “look” for darker wigs, or for their own hair. The powder, usually made from fine flour or starch, was also sometimes tinted blue or lavender. Styling products included beeswax or lard, and orange or herb scents were added to cover the odors of dirt, sweat, and rancid animal products. Wigs had practical benefits. Balding was not only unfashionable, it was also a symptom of syphilis, as were sores and other skin conditions. From the 1500s, the disease spread through Europe, and a wig could help hide these unfortunate symptoms. A wig also helped keep the head clean at a time when lice infestation was common. Men often shaved their heads, and let their wigmakers or servants boil infested wigs for the cleanest possible hair. A King’s Chapel funeral record of 1767 lists Timothy Winship, a Boston peruke-maker, whose profession would likely have combined a maker’s skill and artistry with follow-up cleaning and maintenance. Nov. 12, 1767 saw the loss of Timothy Winship and his wig skills. Wigs also provided a way to display wealth and social status. The amount and color of wig hair, the elegance of hair-dressing, and the elaborate clothes that went with the wig, all reflected the money and leisure necessary for a fine appearance. During the 18th century, wigs became smaller and more restrained. Peter Harrison, architect of the current King’s Chapel, shows this change in fashion. Whether this is a wig or his own powdered hair, the style would be the same, with precise side curls and likely a ponytail, or queue, tied at the nape of the neck. Architect Peter Harrison, done from a 1756 Nathaniel Smibert original: image from Wikipedia King’s Chapel’s first Unitarian minister was a young man when he took the position in the 1780s. In his portrait he wears the same style, called a buckled club, or club, wig, unless that’s his own powdered hair. The side curls are larger than Harrison’s, and the queue behind is more visible. It may be in shadow, or in a wig bag, a cloth accessory into which gentlemen tucked their queues to keep hair powder off their clothes. Reverend James Freeman, by Christian Gullager circa 1794, in the King’s Chapel Parish House Similar wigs appear in film adaptations of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility on the head of Sir John Middleton, a man from the generation before that of the young protagonists. Austen’s “parent” characters were really 18th-century people, after all. I’m a fan of actors Robert Hardy and Mark Williams, each wearing the periwig of their character’s younger days, the former in the Ang Lee film and the latter in the 2008 miniseries. The tight styling of some wigs and the looser, more natural style of others, can be seen together in a scene from The Madness of King George. Some 18th-century wigs were made to resemble a man’s own hair, and some hair was then styled to resemble these wigs. I imagine a Prime Minister having an audience with a monarch might have his wig on. Here King George III (Nigel Hawthorne) and Prime Minister Pitt (Julian Wadham) discuss that the colonies need to be called “America”. The king is not pleased to be reminded! In the 18th century, wigs were a widespread fashion. Even servants wore them as part of their livery, or fancy “working clothes.” Some servants were finely dressed when they served, or stood ready to serve, being the human equivalent of elegant furnishings. Male servants continued to wear wigs as part of their uniforms even after gentlemen abandoned the fashion. In this brief scene from Pride and Prejudice, we see how the bowing servant’s old-fashioned livery and wig stand out among the fashionable gentlemen who no longer wear any such thing. Some well-off Bostonians did not wear wigs in portraits, choosing a more casual look instead. John Singleton Copley’s portraits of Nicholas Boylston and Joseph Barrell show them in banyans (house robes) of rich fabric. Boylston reveals his shaved head under a cap, and Barrell, a King’s Chapel member and current crypt resident, wears his own unpowdered hair or a loosely styled, plain brown wig. These gents may have been moderating or carefully crafting how they showed their wealth. In the Revolutionary period, the desire for political freedom from England was matched by a desire for cultural freedom from the decadence of European fashion and goods. Living a wealthy lifestyle could be difficult for American men who wanted to be seen as serious, virtuous citizens and supporters of the new nation’s ideals. After all, as the Declaration of Independence declared, they had soberly “pledge[d] to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor”. Meanwhile, many lived lives of economic and social privilege to rival the minor English nobility. This print shows the extremes of European excess from which they were trying to distance themselves. Artist Philip Dawe titled it "The Macaroni. A real Character at the late Masquerade". The Macaronis were young English people who pushed luxurious fashion to heights that shocked some of their contemporaries, never mind us today. (The British were actually mocking unsophisticated, unstylish colonists when they sang that Yankee Doodle thought he was a Macaroni just for having a feather in his hat. The colonists adopted the song, added some patriotic verses, and sang it to defy the British troops. So there!) by Philip Dawe, 1773: Image from Wikipedia So newly American men did feel pressure to reject excesses in fashion and personal display. Their clothes, although still of fine fabrics, often had darker colors and less embellishment than the highly embroidered court clothes of the European upper classes. The wig’s loss of popularity in America could be one more response to that pressure. Rejecting imported European fashion partly drove the boycotts on British goods in Boston before the Revolution. The Boston Tea Party was just one example of the intense negative feeling connected to British goods. Meanwhile in Britain, a tax on hair powder after 1795 lessened the popularity of wigs there. The tax was part of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger’s effort to pay for Britain’s wars. Most gents who powdered had to pay one guinea for a certificate from the local Justice of the Peace. Fines were imposed on those miscreants who powdered their wigs or hair illegally. In the 1800s, as all Jane Austen film fans know, many men began just to wear their natural hair. Some men still wore wigs, but fewer and fewer. A number of early American Presidents did, at least in formal settings, but interestingly enough, George Washington’s famous snowy “do” was his own powdered hair, not a wig at all. We are not sure whether he wore a wig or just powdered his hair when he attended a concert at King’s Chapel! For anyone wondering, most English and English colonial women did not wear wigs. The clouds of hair we see in portraits and period dramas were mostly their own long hair with padding inserted for height and shape, plus back-combing, extensions, animal fat, hair powder, and accessories. Women often favored gray, or bluish-gray powder, a lot of volume, and fashionably placed curls, as did the lovely Honourable Mrs. Thomas Graham, painted by Thomas Gainsborough in the 1770s. This interesting video features a step-by-step recreation of such a hairstyle on a patient actor. Image from Wikipedia by Lin A. Nulman, Historic Site Educator This post dedicated to the memory of Amanda Hallay. References and Further Reading: Brekke, Lizzie. “‘To Make a Figure’: Clothing and the Politics of Male Identity in 18th-Century America”. In Gender, Taste, and Material Culture in Britain and North America, 1700-1830. J. Styles and A. Vickery (Eds.). pp. 225-246. Yale UP. 2006. Free, Liv. "Historical Styles- 18th Century Hair Tutorial" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yq4qKsgv8hU Galke, Laura. “Perukes, Pomade, and Powder: Hair Care in the 1700s” Lives and Legacies: Stories from Historic Kenmore and George Washington’s Ferry Farm https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/2015/01/28/perukes-pomade-powder/ Hallay, Amanda. “THE ULTIMATE FASHION HISTORY: The 18th Century” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OsmWUr_iiM Reilly, Lucas. “Why Did People Wear Powdered Wigs?”. Mental Floss https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/31056/why-did-people-wear-powdered-wigs “The Rise and Fall of the Powdered Wig”. American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/head-tilting-history/rise-and-fall-powdered-wig

2 Comments

|

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed