|

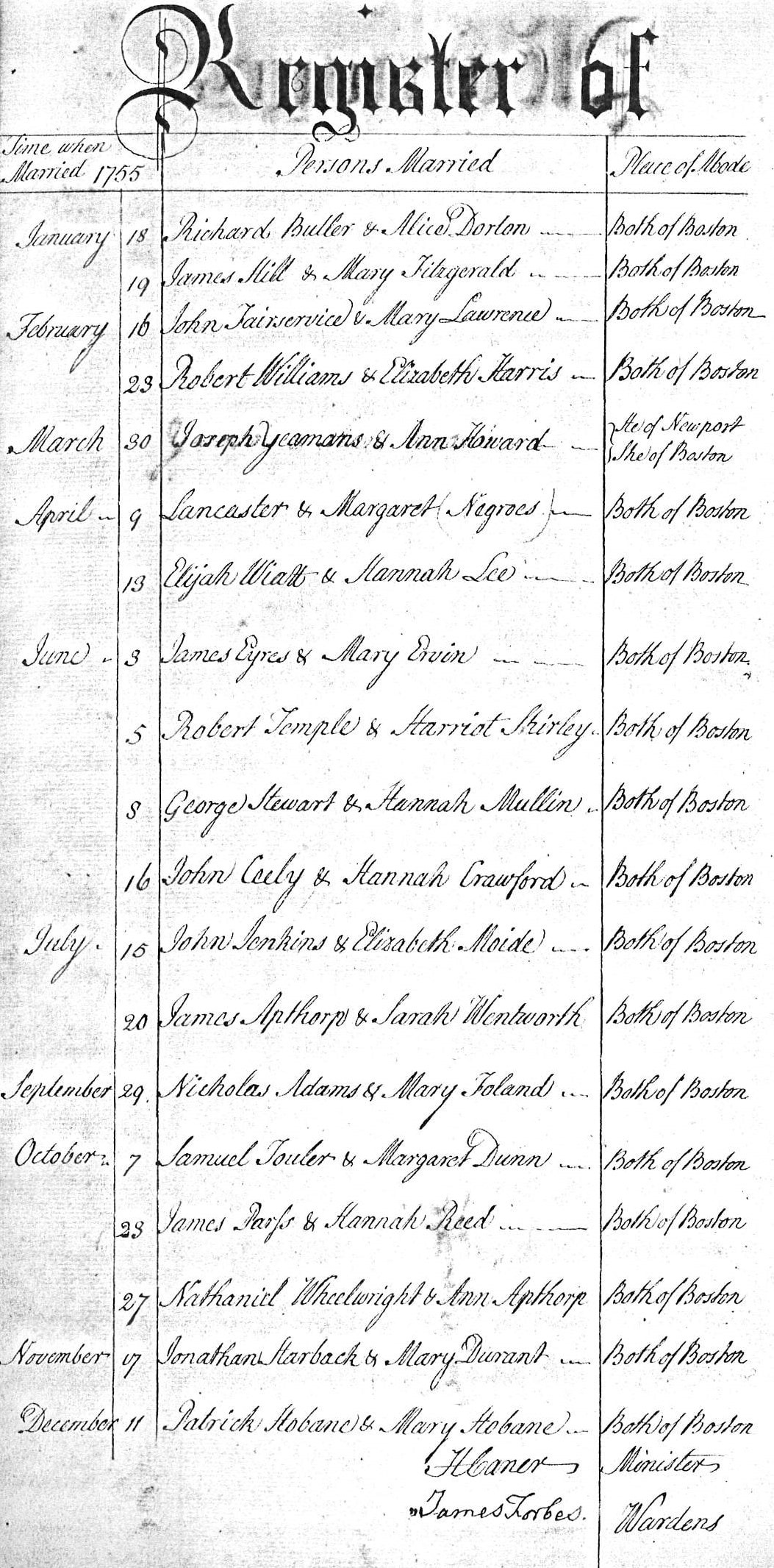

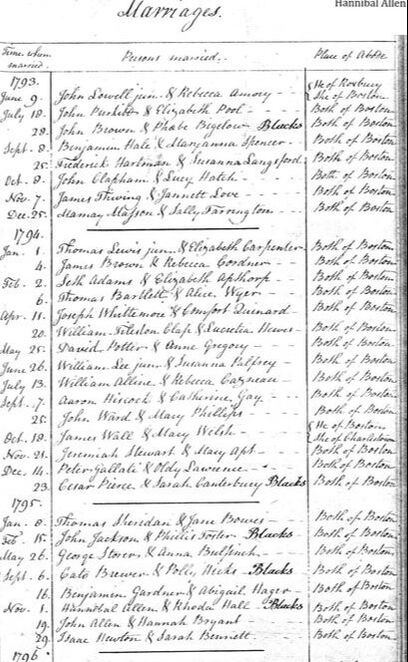

by Lily Nunno, Historic Site Educator IntroductionKing’s Chapel is a space that encompasses many aspects of the history of Boston. This history includes the history of love and romance. As a church, King’s Chapel has been a site of marriages and of memorializing loved ones in stone. Depending on one's societal status, the city's residents, including various members of the King’s Chapel congregation, have experienced love and romance differently. Around Valentine’s Day when we are thinking about our loved ones, we can explore a variety of questions related to love and relationships. How did people engage in romance when facing opposition and challenges? How was marriage not always a positive institution? Slavery, Race, and MarriageAs Boston began to develop as an international port city, enslaved Africans were brought as part of the Atlantic slave trade. Free and enslaved Indigenous people entered the city as refugees from conflicts like King Philip’s War. The majority of the city was white, mainly Puritan settlers. Like other early English colonies, Massachusetts banned relationships between white colonists and those of African descent with the law passing in 1705. The law was updated in 1786 to ban marriages between white citizens and Native Americans. In colonial Boston, many white leaders were concerned with converting people of color to Christianity. They feared the influence and mores of traditional West African and Northeast Algonquin religion which they saw as “dangerous.” In an attempt to convert and instill traditional Christian values in enslaved people, they were married in traditional Christian ceremonies in churches. Several families who attended King’s Chapel enslaved people in Boston and abroad and participated in this practice. Hypocritically, the supposed sanctity of marriage was not respected by enslavers. At any time, an enslaved person could be sold, tearing apart couples and families. The bodily autonomy of enslaved people was not recognized on any level. One of the many impacts of this was the sexually predatory behavior of enslavers directed at enslaved women.

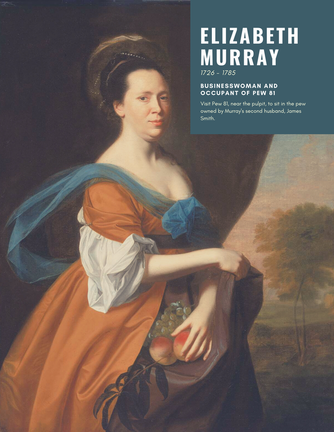

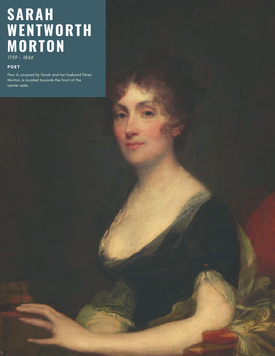

For Black and Indigenous residents of Boston, love and marriage helped build community and connection. But it was also complex especially for enslaved individuals who had little control over their choices and their time. Despite these conditions families like the Hill’s resisted and fought to be together. Gender and Marriage For women living in Boston during the 18th and into the 19th-century, marriage was complex. Marriages gave women little power legally, and women were burdened with social expectations of propriety. Women were expected to be obedient and subservient to their husbands. This was a social expectation and was also often reinforced by religion. The Anglican Book of Prayer which was used at King’s Chapel included a vow that wives made to obey their husbands. Interestingly when revising the Book of Prayer, James Freeman the first Unitarian minister of King’s Chapel removed that vow. While marriage could help raise one's social status, most women in colonial Boston married within their class. Though this was not only the case. In 1742, Agnes Surriage met Henry Frankland, a wealthy baronet; when she was around sixteen while working as a barmaid in Marblehead. Frankland was ten years her senior and decided to become her benefactor and pay for her education in Boston. After four years they began to live together, moving around Massachusetts and later to Europe with Frankland eventually marrying Surriage. Surriage's marriage changed her from being a poor fishing town girl to a wealthy member of the British and Colonial American elite. Her story became the inspiration for works like the poem “Agnes” by King’s Chapel member Oliver Wendell Holmes. While seemingly a “Cinderella” story, Surriage's story was likely more complicated. As a lower-class woman, she had very little control socially or financially in her relationship with Frankland. The initial status of their connection being ward and benefactor also skews the power dynamics of the later romantic relationship.  Portrait of Elizabeth Murray, at the MFA Boston Portrait of Elizabeth Murray, at the MFA Boston Beyond being a promise of love, marriages often brought together business ventures and family fortunes. For example, Grizzel Eastwick brought a lot of familial wealth to her marriage with Charles Apthrop, making one of the wealthiest families in the city. After his death, she retained a fair amount of financial control, unusual for the time. Even if a woman brought income or inheritance to the marriage, her husband would gain financial control over it. A notable exception to this phenomenon is Elizabeth Murray, a member of the King’s Chapel congregation. Elizabeth Murray did not initially come from a wealthy family, moving from Scotland to Boston on her own at the age of twenty-two. From there she started her own business and helped other female entrepreneurs. Elizabeth had three marriages throughout her life, her second husband was much wealthier than her first husband, owning a sugar refinery. For this marriage, she had a prenuptial agreement which allowed her to retain financial control. This was unusual for the time; Elizabeth had an additional prenup agreement for her third marriage as well.  Women were also expected to maintain a respectable image during courtship and not engage in things like premarital sex. However, when comparing birth and marriage records in New England during the 1700s it is clear that many couples were engaging in premarital sex. The upper class of Boston practiced a more rigid form of courtship than their more rural or lower class counterparts. Not only was your reputation put at risk by scandal, but your family’s reputation as well. The marriage of King’s Chapel members Sarah Wentworth Morton and Perez Morton became subject to scandal in 1788. Sarah’s sister Frances came to live with them and became pregnant. This child was believed to be the product of a consensual or non-consensual encounter with Perez. Fearing the impact on her and the family’s reputation Frances committed suicide. For women in Boston in the 18th century and continuing into the 19th-century marriage was not an equal institution. With their husbands holding legal and social power over them. Many women did, of course, experience positive relationships in marriages and some even retain financially and legal control like Elizabeth Murray. But social and religious expectations did hang over them regardless. Sexuality and MarriageToday, queer people have a variety of terms and frameworks to describe their identities. For those in the mid-19th century, labels like “homosexual” did not exist yet; instead it was seen as an action not an identity. Also, spaces for queer people to meet one another, like bars or social clubs, did not start to develop until the 20th century. Nevertheless, there were ways for people who felt same-sex attraction to find romance here in Boston. These relationships could include romantic friendships, “Boston marriages,” and being a spinster/bachelor. While we cannot say that everyone who participated in these relationships was gay or bisexual in the way we understand those identities today, that need not mean they were definitively straight either.

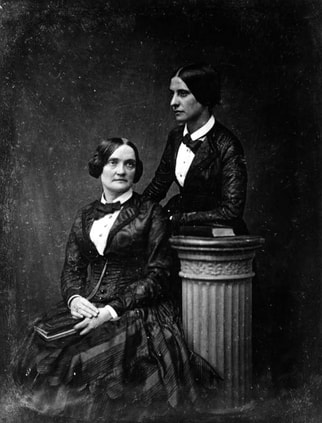

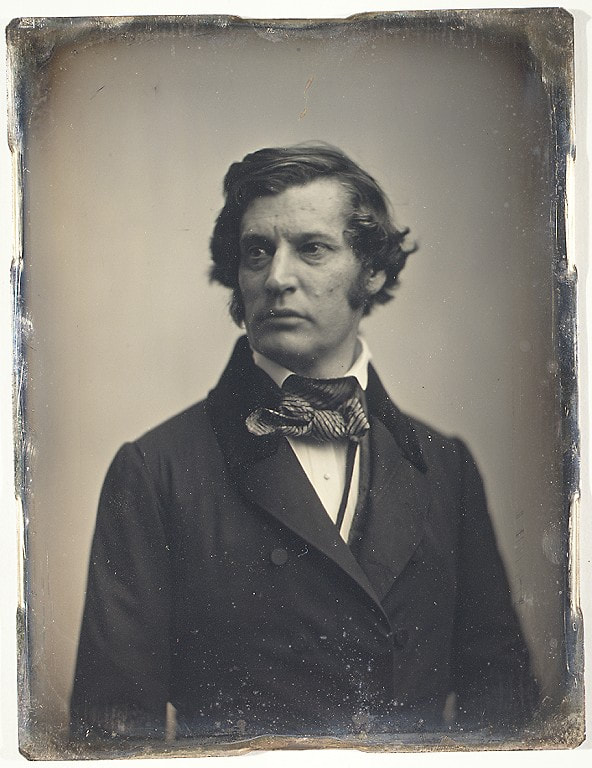

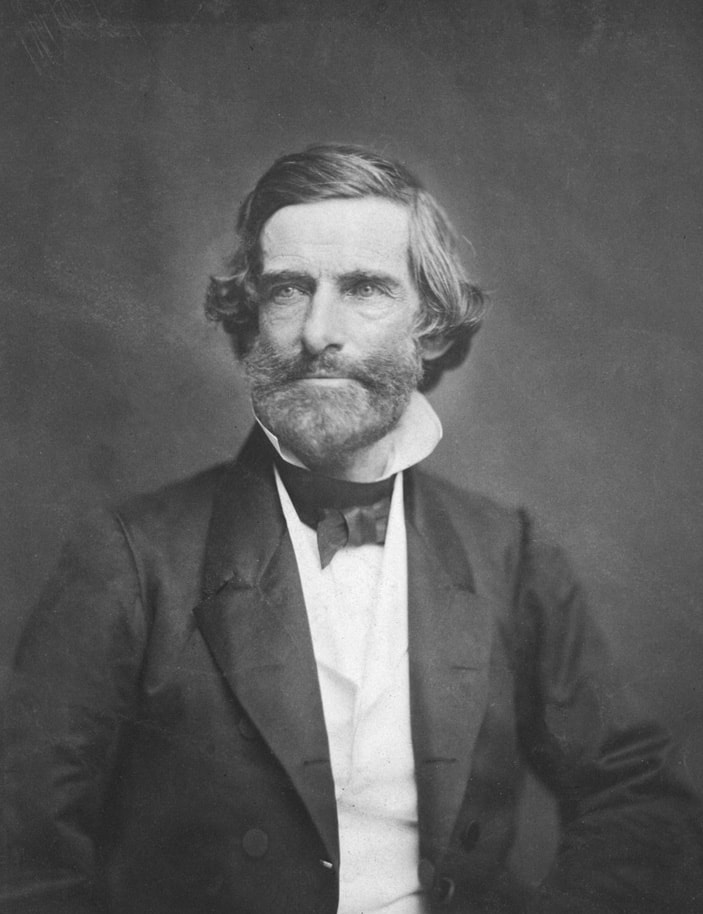

Sumner remained a bachelor for most of his life. Though he was married for a brief period, the union ended in divorce. There were also those men and women who chose never to marry. These men were known as bachelors while unmarried women were labeled as spinsters. Younger unmarried women were at times referred to as spinstress. While the decision to not marry could be the result of many things from unluckiness in love, to a desire for independence, or focusing on one's career. But others may not have wanted to commit to heterosexual marriage.  Charlotte Cushman (left) and Matilda Hays (right) Charlotte Cushman (left) and Matilda Hays (right) King’s Chapel was also the site of the funeral of Charlotte Cushman, who died next door at the Omni Parker Hotel. Cushman was a famous actress and widely known for playing both male and female roles. Cushman also publicly lived with and had relationships with various women. There are several examples of unmarried women living together in the Boston area publicly. The term “Boston marriages” would come to describe these relationships originating from a Henry James novel. Often these were educated women from upper or middle-class families whose professions or background allowed them financial independence. For example, Anne Fields, a friend of several local literary figures like King’s Chapel member Oliver Wendell Holmes, lived with poet Sarah Orne Jewett for thirty years after her husband died. These women were able to have these relationships publicly partly because of the societal belief that women did not experience sexual desire. Until homosexuality became medicalized and concepts like the ‘invert’ emerged being in the late 1800s these relationships could exist without scrutiny. For Bostonians in the mid 19th century, there were ways to engage in same sex romance and avoid heterosexual marriage. But there were though often economic barriers to some of these choices like spinsterhood and Boston marriages. Alongside the social pressure of the importance of marriage and family. It is also important to note the cultural understanding and practices of Indigenous and Black queer people may have differed from their white counterparts. Sources:"Agnes Surriage and Her Journey from Tavern Wench to Lady of the Manor," New England Historical Society, https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/agnes-surriage-journey-tavern-wench-lady-manor/

"An Era of Romantic Friendships: Sumner, Longfellow, and Howe, Longfellow" House Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site, NPS https://www.nps.gov/articles/an-era-of-romantic-friendships-sumner-longfellow-and-howe.htm "Boston Marriages," Longfellow House Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site, NPS https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/boston-marriages.htm Horton, James O., Horton, Lois E., and Horton, Lois E.. In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700-1860. New York: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1996. Accessed January 2, 2022. Mandell, Daniel R. "Shifting Boundaries of Race and Ethnicity: Indian-Black Intermarriage in Southern New England, 1760-1880." The Journal of American History 85, no. 2 (09, 1998): 466-501. The Elizabeth Murray Project, California State University, https://web.csulb.edu/colleges/cla/projects/EM/ "The 1788 Scandal of Fanny Apthorp Never Dies," New England Historical Society, https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/1788-scandal-of-fanny-apthorp-never-dies/

2 Comments

Barbara Pearson

2/27/2022 08:33:40 pm

So very interesting! I had no idea of these relationships in the 1800-1900 era. Thanks for writing.

Reply

3/7/2023 12:23:42 am

Whether you’re looking for an Italian vineyard wedding, a Catholic church wedding, a grand Italian castle, a private wedding villa, an exciting destination wedding in Rome, or a legally recognised beach wedding on Italy’s beautiful coast, we have them all.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed