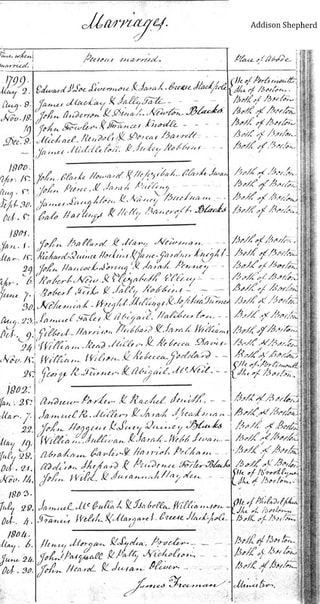

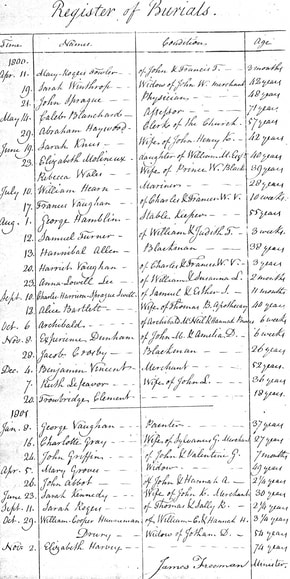

Compiled by Jennifer Roesch using research by Faye CharpentierThe King’s Chapel History Program is committed to continuing to include the voices of African Americans and other historically marginalized people in their interpretation and tours. When visiting the chapel, we encourage visitors to engage with these primary sources featuring these African Americans, beyond the historic site's Black History Month programming. This February in honor of Black History Month, the King’s Chapel History Program shared with visitors the stories of some of our 18th and 19th century African American congregants. Inside the sanctuary and on social media, visitors explored how primary sources have informed our research and made it possible to learn about historically marginalized people through church and other archival records. African Americans have been marginalized throughout history not only through their omission in history books, but also through the lack of information found in archives. Thanks to the growing effort to digitize records as well as finding materials related to African American history, we have been able to begin to learn about the various lives of African Americans at King’s Chapel. Here are some of the people we highlighted this month who had ties to 18th and 19th century King’s Chapel: Dinah An African American woman named Dinah (at least the name given to her by her enslaver) has several ties to King’s Chapel in the 18th century. Dinah was a woman enslaved by Dorothy Wharton, a King’s Chapel member who owned pews in both the original wooden and current stone building. While her white enslaver had the luxury of owning a box pew in the main sanctuary level, Dinah would have been forced to sit alongside the other free and enslaved African Americans in the upstairs “gallery” section. According to our records, Dinah was baptized as an adult at King’s Chapel on December 25, 1739. Shortly after, she married Joseph, a man enslaved by Thomas Palmer (not listed as a King’s Chapel proprietor), on January 3, 1740. Our records also suggest that Dinah and Joseph had a baby. Jane, identified in the church’s baptismal register as “Negroe, Serv of Dorothy Wharton. Infant” was baptized on October 17, 1740, just 10 months after Dinah and Joseph married at King’s Chapel. After Dinah and Joseph’s marriage record and baptism record of their possible child Jane, we do not know what happened to the family. Despite being married, Dinah and Joseph would have probably not lived together because they were enslaved by different people. Slavery was not abolished in Massachusetts until several decades after Jane’s baptism, so we do not know the fate of Dinah and her family.  Page from the King's Chapel Register of Marriages showing Addison Shepherd and Rhoda Hall's wedding Page from the King's Chapel Register of Marriages showing Addison Shepherd and Rhoda Hall's wedding Addison Shepard Addison Shepard is the only African American whom we know was baptized, married, and buried by King’s Chapel in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Shepard was born at a time when slavery was still legal, but we do not know if he was a free or enslaved man; he first appears in our King’s Chapel records in 1798, sixteen years after slavery was abolished in Massachusetts. On August 19, 1798 Shepard was baptised as an adult. Four years later, on October 21, 1802, he married Prudence Foster at the chapel. So far we have not found any other records for Shepard’s wife, and the couple is not listed as having children. Eleven years after marrying Foster, Addison Shepard passed away, and his burial was held by King’s Chapel on May 17, 1813. While this is a small amount of information, it is notable, as it indicates that Shepard had a sustained relationship with King’s Chapel for at least 15 years, possibly as a regular attendee to worship. However, churches throughout the region, like at King’s Chapel, continued to segregate congregants based on their race. Addison and his wife Prudence would have been forced to sit in the upstairs gallery during services.  Page from the King's Chapel Register of Burials, relating to the death of Hannibal Allen Page from the King's Chapel Register of Burials, relating to the death of Hannibal Allen Hannibal Allen Hannibal Allen and Rhoda Hall’s connection to King’s Chapel begins when they got married in the early 1790s. The African American couple were born in the 1760s, a time when slavery was still legal in Massachusetts. Were they enslaved or free during before the abolishment of slavery in 1783? Unfortunately, we haven’t been able to locate any records providing any information about them prior to their link to King’s Chapel. The couple, however, had less than a decade together when Hannibal Allen died at 38 years old and was buried by King’s Chapel on August 13, 1800. Records at the New England Historic Genealogical Society have given us the ability to learn more about Hannibal and Rhoda. Shortly before his death, Hannibal purchased property in Beacon Hill. The lot, located where Smith Court is today, was formerly the site of a ropewalk. Today, Smith Court is off of Joy Street and adjacent to the Museum of African American History. Allen and several other members of the African Society purchased and resold lots of land there. Therefore, it is likely that Allen and Hall lived in Beacon Hill. Allen’s involvement in the African Society is notable. Established in 1796, the African Society was “a group of African Americans organized to provide a form of health insurance and funeral benefits, as well as spiritual brotherhood, to its members” (MHS). A document of “Laws of the African Society” held at the Massachusetts Historical Society outlines membership fees, benefits, and requirements for participation in the society. Much emphasis is placed on helping support the families if a member of the society passed away. The final page of the document lists forty-four charter members of the African Society, including Hannibal Allen.

Another paper in the materials shares that Mr. Parker also dug Flora's grave and John Low placed Flora in her coffin. We also learn that Flora was ill at the time of her death from a record of payment of $96.45 to Doctor James P. Chaplin “for medicines and attendance in the decd’s last sickness.” In a letter dated June 1, 1815, Flora’s daughter Susanna Marandy wrote to probate judge James Prescott and requested that Primus Hall be appointed as the administrator of Flora’s will, explaining that two of Flora’s children, John and Margaret were still minors. “Primus Hall of said Boston, soap boiler,” as Susanna described him, was the son of famed black leader in Boston, Prince Hall. In addition to learning the names and approximate ages of Flora’s Children, the paperwork lists her place of residence as Charlestown where she owned “part of a house consisting of one lower room and the cellar under it, and a lot of land adjoining the same of about fourteen square nods.” Flora’s possessions -- including her home, a tin candle box, iron kettle, four chairs, an old feather bed, and a looking glass -- were valued at just over $251.88, roughly $4,050 in today’s buying power. Unfortunately for the executor of her state and her family, the costs of her funeral, debts, and fees paid for the inventory of her estate exceeded the value of her estate by $32.88, or approximately $530. While most of her real estate and household possessions were sold by Primus Hall at auction, the fate of her children is not included in the paperwork. The King’s Chapel History Program is committed to continuing to include the voices of African Americans and other historically marginalized people in their interpretation and tours. When visiting the chapel, we encourage visitors to engage with these primary sources featuring these African Americans, even beyond Black History Month.

1 Comment

|

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed