|

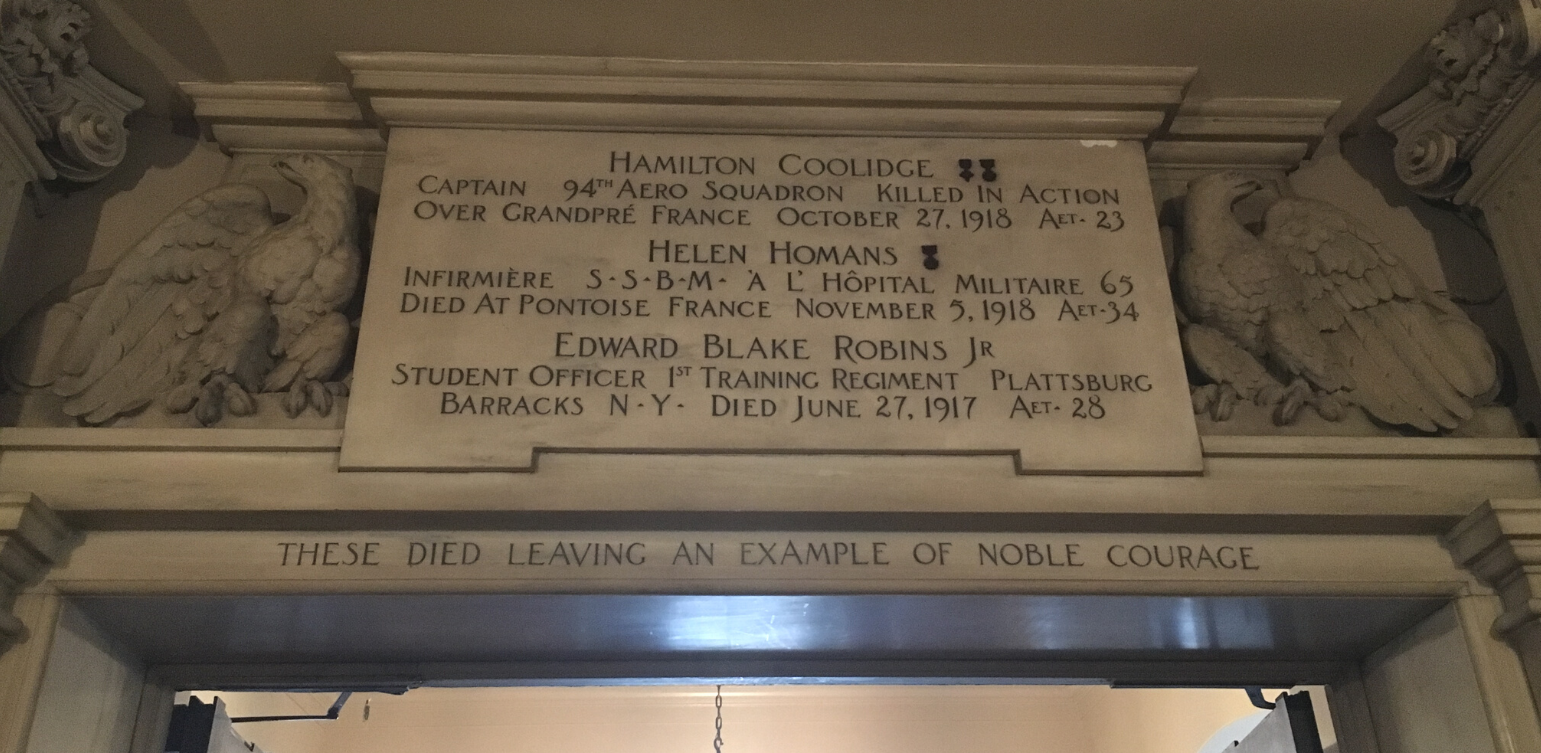

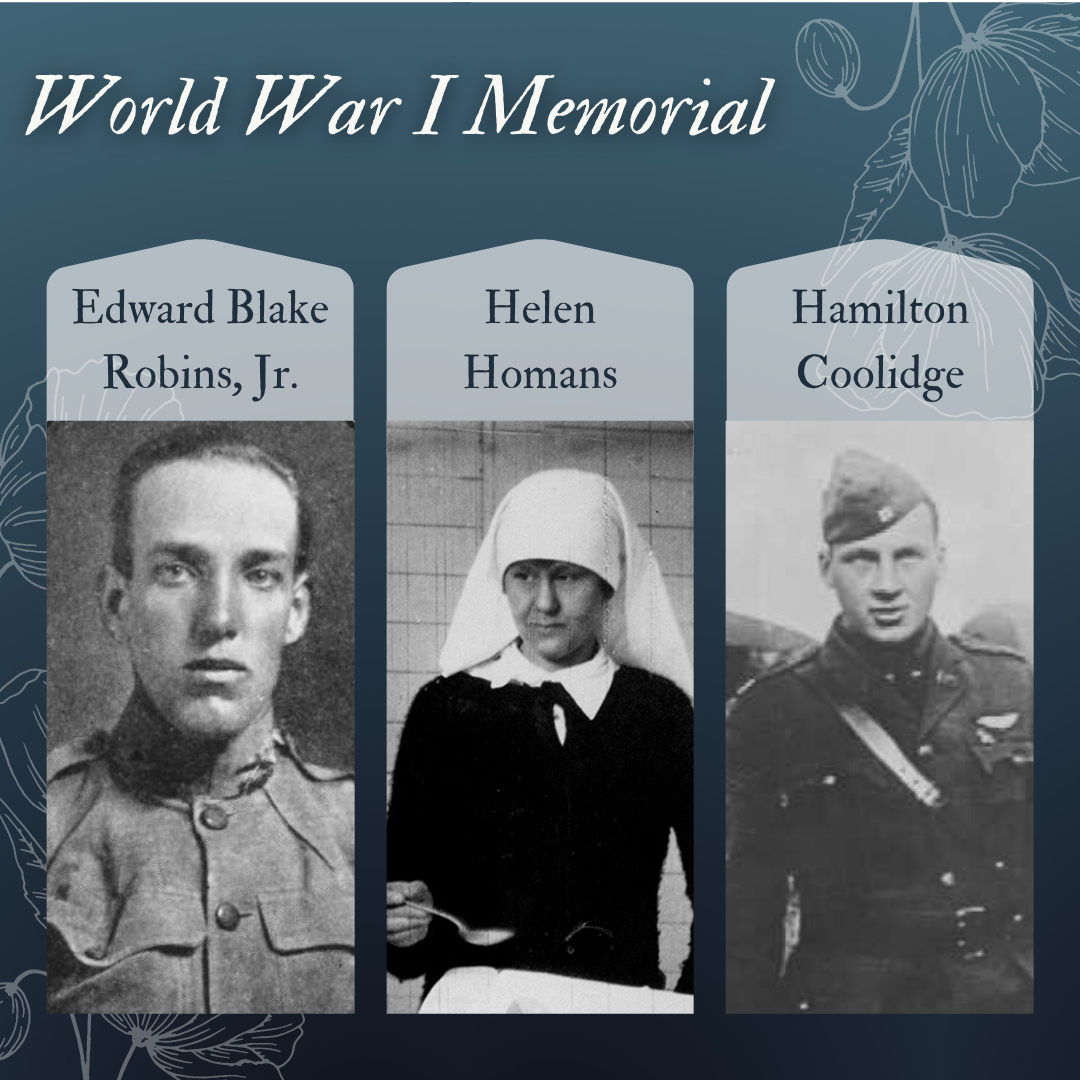

Veterans Day, the anniversary of the November 11, 1918 Armistice that brought the First World War to an end, provides an opportunity to reflect on King’s Chapel and its community during World War I. Within a month of the Armistice, King’s Chapel formed a Committee on the War Memorial, dedicated to erecting a permanent memorial honoring King’s Chapel members involved in the war. The memorial, as seen today, was the culmination of several years of discussion and planning – it was ultimately unveiled and dedicated on November 11, 1925. During those years, the committee revealed their own understanding of how a memorial serves a dual role of honoring a recipient, while preserving the attitudes and values of the community and era that created it. For example, the committee debated whether to honor all members who served in the military during the war, or just those who lost their lives. Should they create a static memorial such as the marble archway that exists today or, maybe, a living memorial, such as a proposed annual lecture series during Lent? Ultimately, the decision was made to honor 3 individuals who died in service of the U.S. Military or while working abroad during the war. The memorial was to be erected with funds raised by the committee, not the congregation, leaving much of the fundraising efforts to the families of those being honored. This is how the church, 100 years ago, wanted their community to be remembered, through the stories of 3 individuals (pictured below): Edward Blake Robins, Jr., Hamilton Coolidge, and Helen Homans. King’s Chapel’s monthly calendar, circulated shortly after the war’s close, began the work of memorializing its members. After expressing the community’s sadness in the losses experienced, the Reverend Howard Brown wrote that King’s Chapel “also has a right to cherish a very noble pride in their accomplishments and their memory. [They] gave themselves without reserve to the cause for which the nation fought, and the service that they rendered displayed rare courage and intelligence.” Edward Blake Robins, Jr. Edward Blake Robins, Jr. was born in March of 1889 to a military family – his father had served in both the Civil War and the Spanish-American War. From a wealthy Boston family, Robins entered Harvard University, graduating in 1910. During his school years, Edward was deeply involved on campus, engaged in many clubs and activities, including the Hasty Pudding Institute which still exists today. After leaving school he started working for the Portland Railway, Light, and Power Company. In 1915, Edward enlisted in Troop B of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia Cavalry, and was deployed to the Texas-Mexico Border the following summer during the Mexican Revolution. After returning to Boston, Edward entered Reserve Officers Training at Plattsburg, New York in May, 1917 – just weeks after the United States entered World War I. Unfortunately, he had unknowingly contracted amoebic dysentery while stationed in Texas. Despite severe abdominal pain, Edward continued to pursue his training, but underwent emergency surgery for what doctors suspected was appendicitis at the end of May. During the operation, the true cause of his illness was determined. After being discharged and transferred to Massachusetts General Hospital, Edward Blake Robins, Jr. died in his home state of Massachusetts on June 27, 1917. He was 29 years old. While he was not killed in battle, Robins is remembered for his physical and mental endurance, and refusal to shirk what he saw as his responsibility to his country, despite looming illness. During the war, King’s Chapel included his name on their makeshift Roll of Honor, along with the names of at least 32 other members who were fighting for their country. Hamilton Coolidge

Coolidge understood the dangers of war, and experienced a great loss when his friend Quentin was killed in action. But Coolidge wrote in a letter home that “Death is certainly not a black unmentionable thing, and I feel...that dead people should be talked of just as if they were alive...To me Quentin is just away somewhere...I miss him the way I miss Mother and the family, for his personality or spirit are just as real and vivid as they ever were.” This is how Coolidge chose to offer his personal memorial to his friend. On October 27, 1918, Ham’s plane took a direct hit from an anti-aircraft shell near Grandpre, France. As shared with the King’s Chapel congregation several months after Ham’s death: Ham was “one of the four New England heroes cited recently for extraordinary acts of bravery and awarded the distinguished service medal...Leading a protection protocol of the squadron, Captain Coolidge went to the assistance of two observation planes which were attacked by six German machines. Observing this maneuver, the enemy sent up a terrific barrage from anti-aircraft guns. Disregarding the extreme danger, Captain Coolidge dived straight into the barrage, and his plane was struck and sent down in flames. “ He had just turned 23 years old. A fellow pilot named Eddie Rickenbacker and a priest were able to locate Ham’s body and give him a proper burial. In his memoirs, Rickenbacker shared: “Amid the continuous whines of passing shells we laid the poor mangled body of Captain Hamilton Coolidge in its last resting place. Over the grave was placed a Cross suitably engraved with his name, rank and the date of his tragic death. A wreath of flowers was laid at the foot of the cross. Then with uncovered head I took a photograph of the grave, which later was sent "back home" to the family who mourned for one of the most gallant gentlemen who ever fought in France.” Helen HomansOf Helen Homans, the second name on our memorial, it was said that “She gave her life for France in the World War just as truly as though she had been killed serving upon the field of battle.”  Helen was born in 1884, and came from a medical family, with doctors going back to the 1700s. During her life, much of her family, including her brother and father, worked at MGH. After studying at Radcliffe, Helen became extremely involved in volunteer work at the hospital. She served on the Board of Visiting Ladies, volunteered with the Social Service Department, worked intensely with tuberculosis patients, and even continued to volunteer at MGH during her brief periods of time back from France during the war. Of her personal life, research done by the Canton Historical Society shares that Helen raised Russian Wolfhounds while her family summered there. Before the war, Helen had spent time travelling in France, and fell in love with the country. When hostilities broke out, she went to France to volunteer at a field hospital in May 1915, two years before the United States entered the war. For the next 3 years, Helen worked at a number of military hospitals, field hospitals, evacuation hospitals, and Ambulance units throughout France. In just a few short years, she had gone from a hospital volunteer in Boston to a full-fledged nurse overseeing her own unit in France. Unfortunately, she died from Spanish Influenza on November 5, 1918, just days before the Armistice. She was 34 years old. Helen was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm, a prestigious honor in the French military. The citation, signed by a major general (Philippe Petain), noted: “With the armies since the twenty-nine of February 1916, she has been noted for her absolute devotion to duty.” While her name was included in our 1925 memorial and a memorial plaque was dedicated in her honor at Massachusetts General Hospital’s library, her name was not added to Harvard’s Memorial Church until much later. Although the Memorial Chapel itself was dedicated on Armistice Day 1932 in memory of those from Harvard who died in World War I, Helen’s name was excluded until 2001, when Helen and two other Radcliffe women were finally recognized for their role in the war. Sources: Comeau, George T. "True Tales: A Hero's Service," Canton Citizen, May 16, 2013.

Comeau, George T. "True Tales: Helen Homans ~ A Hero's Death," Canton Citizen, June 14, 2013. Coolidge, Hamilton. Letters of an American Airman: Being the War Record of Capt. Hamilton Coolidge, U.S.A., 1917-1918. Boston, 1919. Howe, M.A. DeWolfe. Memoris of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany, Vol. II. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921. Perkins, John Carroll. The Annals of King's Chapel, Vol. III: 1895-1940. Boston. 1940. "Through Her Eyes: Katharine McLennan," Online Exhibit from Beaton Institute, Cape Breton Regional Library, Fortress Louisbourg Association and Parks Canada World War I - Women of Radcliffe College

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed