By Jennifer Roesch and Faye CharpentierHistory Program Assistant and Program Director

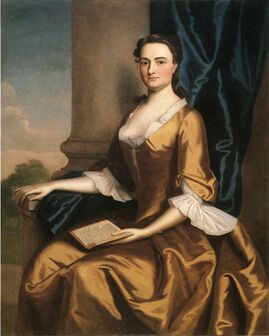

When an Anglo-American died in the 18th-century, there were usually several sets of rituals associated with funerals and burials. Instead of going to a funeral home, families would prepare the body themselves and have visiting hours to allow families and friends to view the body in their own home. During the viewing, people shared remembrances of the deceased and met with the grievers. While Puritans would then carry the body to a burial ground, such as the one located next to King’s Chapel, for a small, private burial, Anglicans headed into the church for a burial service.  From Charles Apthorp's memorial sermon (Massachusetts Historical Society) From Charles Apthorp's memorial sermon (Massachusetts Historical Society) Thanks to published sermons, we know that Anglican ministers, including those at King’s Chapel, preached memorial sermons. Instead of talking directly about the person’s life and remembering them, the ministers often used the deceased as an example of a strong Christian and discussed the type of person members of the faith should strive to be. A good example of this is a sermon the Reverend Henry Caner preached in 1758 after the death of the wealthy King’s Chapel member, Charles Apthorp. In his sermon, Rev. Caner explains how Charles Apthorp exemplified a Christian life: "...He [Apthorp] was an old, try’d, steadfast disciple, and Son of the Church of England; and he took great pains and used his best endeavours to educate his children and family in a strict adherence to it, as that which he himself was firmly persuaded of, and found much comfort in." As described in the sermon, Charles Apthorp was a wealthy member and lay leader of King’s Chapel for several decades. Our burial records and his probate inventory reveal at least seven people enslaved by Charles Apthorp. The Apthorp family papers, located at the Massachusetts Historical Society, provide insight into the expanse of the family’s business and wealth. Numerous letters inform us about his continuous trade with the West Indies, supplying various goods to stock his shop located in Merchants Row.  Portrait of Grizzell Eastwicke Apthorp by Robert Feke (DeYoung Museum of Art) Portrait of Grizzell Eastwicke Apthorp by Robert Feke (DeYoung Museum of Art) On January 13, 1727, Charles married Grizzell Eastwicke, the daughter of a wealthy sugar plantation owner and enslaver, at King’s Chapel. The couple had a total of eighteen children and sat in adjacent pews in the chapel, stretching from aisle to aisle. When Charles died suddenly in 1758 at age 60, Grizzell and their children likely made the plans and preparations for Charles’ funeral at King’s Chapel. Thanks to the rise of the Anglican church in Boston, large funerals like Charles Apthorp’s at King’s Chapel, became increasingly common throughout the mid-1700s.  White leather funeral gloves (Connecticut Historical Society) White leather funeral gloves (Connecticut Historical Society) Along with these grander funerals, it became increasingly common to give out gloves, essentially acting as party favors, which is arguably one of the most unique mourning traditions throughout early American history. Gloves were initially given just to pallbearers and ministers not only as a token of remembrance and respect, but also to literally keep their hands clean.. As gloves (originally an accessory of the wealthy and elite) became increasingly affordable by the mid-1700s, nearly all attendees at New England funerals would have received a pair of white leather gloves. White was most popular for funeral gloves because of surviving examples of funeral gloves and newspaper advertisements from the time period, such as this pair held by the Connecticut Historical Society.  List of Gloves Given at Charles Apthorp's Funeral (Charles Ward Apthorp Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society) List of Gloves Given at Charles Apthorp's Funeral (Charles Ward Apthorp Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society) iving gloves was seen as a way to strengthen community relations by showing respect for the deceased and those who honored them by attending their funerals. By the 1730s this was so common that a pauper’s funeral included 7 pairs of gloves, while over 4,000 pairs were given out at Peter Faneuil’s uncle’s funeral. Charles Apthorp’s own family gave out 95 pairs of gloves, as shown in the image below, when he passed away. The glove recipients included both immediate and distant family members, as well as other distinguished people in the Boston community. The local government in Massachusetts actually tried several times to regulate gift-giving at funerals because it was becoming too expensive and putting such a large burden on middle- and lower-class families, but the practice did not completely end until after the Revolution.  Apthorp Family Tomb, located in the King's Chapel Crypt Apthorp Family Tomb, located in the King's Chapel Crypt Even in death, family and loved ones remained nearby. At the end of Charles Apthorp’s funeral, his coffin was likely placed in the Apthorp family tomb (number 2), located in the crypt beneath the Chapel. While we do not possess a detailed list of crypt occupants, we can presume that Charles was laid to rest alongside the three children and one grandchild who died before him. It was not customary for families to visit the tombs and burial sites of loved ones during the 18th-century, but visitors at King’s Chapel can now see these tombs through our ticketed Bells and Bones tours as well as during our after-hours candlelight crypt tours.

While the description of Apthorp as “a most upright merchant” likely refers to his style of honest business practices, it is ironic today, as we know he dealt extensively in the slave trade. This statement exposes how commonplace slavery was in mid-18th century Boston — a man who profited heavily from selling and enslaved people and who stocked his shop with goods produced by enslaved labor was still considered an honest merchant. The mourning and memorialization of King’s Chapel member Charles Apthorp is just one story that’s highlighted in our daily Bells and Bones tours and in our special February "Till Death Us Do Part" and October "Tales from the Crypt" candlelit tours. We invite you to learn more about the other families of King’s Chapel of the 18th- and early 19th-centuries who are in our crypt below or memorialized in the sanctuary. More information about tour times and tickets are available online here. Sources:

Caner, Henry. The nature and necessity, of an habitual preparation for death & judgment. A Sermon Preached at King’s-Chapel in Boston, November 21, 1758 Upon occasion of the death of Charles Apthorp, esq. Boston: New-England: Printed by John Draper, 1758. Charles Ward Apthorp papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Boyle, Issac. A Historical Memoir of the Boston Episcopal Charitable Society. Boston: I.R. Butts, 1840. Bullock, Steven C. “‘Often concerned in funerals:’ Ritual, Material Culture, and the Large Funeral in the Age of Samuel Sewall.” In Volume 82: New Views of New England: Studies in Material Culture and Visual Culture, 1630-1830, edited by Martha J. McNamara and Georgia B. Barnhill, 181-211. Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2012. Bullock, Steven C. and Sheila McIntyre. “The Handsome Tokens of a Funeral: Glove-Giving and the Large Funeral in Eighteenth-Century New England.” The William and Mary Quarterly 69, no. 2 (April 2012): 305-346. Foote, Henry Wilder. Annals of King’s Chapel: From the Puritan Age of New England to the Present Day. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1896. Goody Clancy, Historic Structures Report for King’s Chapel, 2006. King's Chapel (Boston, Mass.) records, Massachusetts Historical Society. Nehama, Sarah. In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2012. Tate, Thad. “Funerals in Eighteenth Century Virginia.” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series--0085. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library. Williamsburg: 1990.

1 Comment

I like that you talked about having descriptions like a most upright merchant which shows that a person has been honest when it comes to their business practices. I think that is a great idea if you are going to have certain details engraved on your markers or when you work with a monument service professional. My mom should know about it so that she can consider it for the funeral of my grandmother who recently passed away.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed