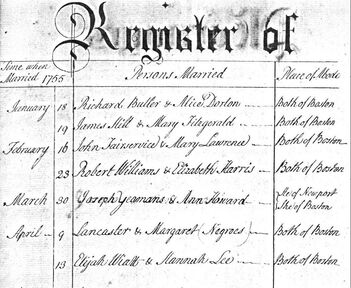

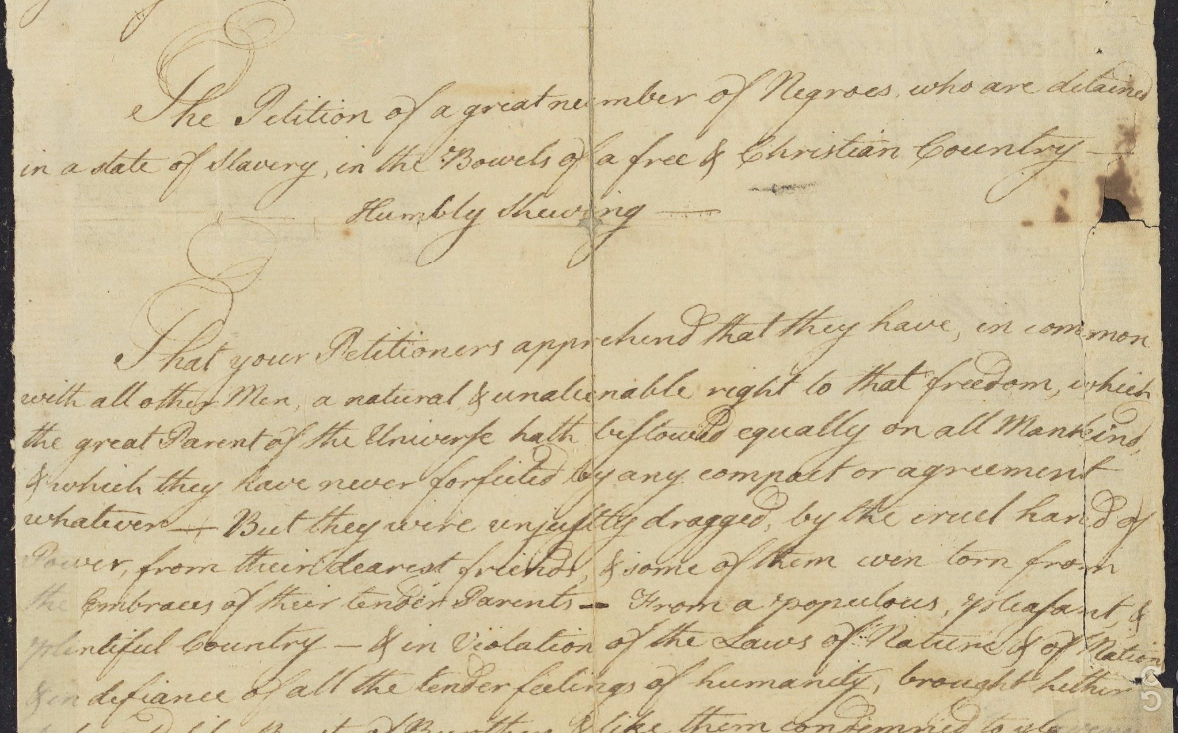

By Christina RewinskiHistoric Site Educator  Since the dominant historical narrative in Boston, especially among sites on the Freedom Trail, revolves around the American Revolution, visitors frequently want to know how King’s Chapel history connects to stories of heroic Patriots fighting against oppressive British rule. While certain members of King’s Chapel fit this mold, the colonial congregation consisted of a financially, racially, and politically diverse group of people, each of whom reacted differently to events in the late 18th century. By comparing the words, actions, and experiences of two men of King’s Chapel during this time--Perez Morton and Lancaster Hill—it becomes clear that individuals define freedom in vastly different ways and their attempts to gain freedom vary greatly, even as they show a similar focus and passion for their cause.  Engraving of Perez Morton by C. B. J. F. de Saint-Mémin National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute Engraving of Perez Morton by C. B. J. F. de Saint-Mémin National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute At King’s Chapel, Perez Morton is the epitome of the classic Boston Patriot. He was among the few congregants who remained in Boston through the American Revolution and returned to the church afterwards, purchasing pew four, in a prime central location in the church. Morton was elected churchwarden and joined one of the church’s most influential families through his marriage to poet Sarah Wentworth Apthorp, whose relatives were longstanding members and benefactors of King’s Chapel. Morton’s influence and connections extended outside of the church community. He was a lawyer who was an active member of the Committee of Safety and the Committee of Correspondence. These groups consisted of colonial Patriots working to establish the systems needed to form a new, independent society. Morton’s participation allowed him to forge relationships with some of the most famous Patriots in Boston, including Dr. Joseph Warren, a notable physician, politician, and leader, who died at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June of 1775. Months later, after Warren’s body was identified, his funeral was held at King’s Chapel where Perez Morton gave the eulogy for his friend. On April 8, 1776, Morton gave his speech to an audience he viewed not simply as mourners of the heroic Dr. Warren, but potential colleagues in the ongoing fight for American independence. He framed Warren’s death as an opportunity, rather than a tragedy, insisting: “Now is the happy Season, to seize again those Rights, which as Men we are by Nature entitled to, and which by we never have and never could have surrendered:—But which have been repeatedly and violently attacked by the King, Lords and Commons of Britain”. He then urged all listeners: "Go tell the King, and tell him from our Spirits, Throughout this eulogy, Morton maintained that so long as the colonists fight to assert their rights and sever ties with the British, “the Name and the Virtues of WARREN shall remain immortal.” Perez Morton’s words were dramatic and memorable, yet the sentiment behind his speech would not have been unfamiliar to his audience. Other orators of this time relied on emotional, provocative imagery to move their listeners to action. For instance, the evocation of the chains of slavery as a metaphor for the oppression faced by colonists was commonplace, an ironic comparison considering the great number of individuals in colonial America whose lives were shaped by slavery, while many of those speaking for independence were enslavers. To people of color in the colonies, enslaved or otherwise, a fight for freedom meant something more than establishing a new nation.  Lancaster and Margaret Hill’s union is included in King’s Chapel’s marriage register for 1755 Lancaster and Margaret Hill’s union is included in King’s Chapel’s marriage register for 1755 Lancaster Hill was one such man, a free black congregant of King’s Chapel whose time at the church overlapped that of Perez Morton’s, though their experiences would have differed greatly. While Morton sat in a sanctuary pew reserved for his family and guests, Hill was not granted that luxury. As a black man, Lancaster Hill was forced to sit in the gallery pews during services, with all other people of color, including free and enslaved indigenous and black congregants. On April 9, 1755, Lancaster Hill married a woman named Margaret at King’s Chapel. Margaret Hill was enslaved by Silvester Gardiner, a white congregant, so when the Hills had children, they too were enslaved from birth. Recognizing how tenuous his family’s fate was while left in Silvester Gardiner’s control, Lancaster Hill used the savings he earned at his shop on Marlborough Street to purchase freedom for some of his children. Even as a free man, Hill felt the confines of slavery; when the Gardiners moved to Trinity Church, taking Margaret and the children with them, Lancaster soon followed to attend services with his family. Amidst the tumult of events throughout Boston in the 1770s, Lancaster Hill started to collaborate with other men of color, who, like him, sought legal freedom for enslaved members of their community as well as to combat the racial prejudices that denied even free black men the opportunities available to their white counterparts. Eventually, through these meetings, Hill met formerly enslaved abolitionist Prince Hall. In 1777, Hall led a group of men in creating a petition to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in response to aspects of the Declaration of Independence they found lacking. Lancaster Hill was among the group of seven men working alongside Hall in this endeavor, and was, in fact, the first man to sign said petition. Their document contains similar wording to both the Declaration of Independence and Perez Morton’s eulogy for Dr. Warren, in an effort to make the legislators to whom it was presented see the hypocrisy of their words and actions. Though Prince Hall, Lancaster Hill, and the other petitioners hoped their work would lead the Massachusetts legislators to pass a law ending slavery, the state did not abolish slavery until 1783, and the institution remained legal in parts of the United States until the mid-18th century. Throughout his life, Lancaster Hill supported efforts to establish equality for all people in the United States, understanding that separating from a tyrannical government, creating a new nation, or even the abolition of slavery were not enough to ensure that the universal, “unalienable right to freedom” was actually granted. Lancaster Hill and Perez Morton are far from the only people who were determined to do all they could to obtain the freedoms they thought they and their peers deserved, either in their time or since. Their stories serve as a reminder of the many interpretations of freedom that exist even within a single community. A comparison of these two men’s stories to those of other people seeking freedom throughout American history shows the need to consider multiple interpretations of freedom and to be open to expanding these interpretations to create a just society. How do you define freedom today, in the 21st century? What freedoms would you like your community to work toward in the future? Sources: de Saint-Mémin, Charles Balthazar Julien Févret. “Perez Morton, 1807.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_S_NPG.74.39.11.41

“Doctor Joseph Warren.” National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/warren.htm “Gilbert Stuart: Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton), 1802-20.” Worcester Art Museum. https://www.worcesterart.org/collection/Early_American/Artists/stuart/sarah/discussion.html Hanson Plass, Eric M., Lancaster Hill’s Revolution. Lecture presented at: King’s Chapel; March 8, 2020; Boston, MA. Hanson Plass, Eric M., "“So Succeeded by a Kind Providence”: Communities of Color in Eighteenth Century Boston" (2014). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 270. Pages 109-120. King’s Chapel (Boston, Mass.) records, Massachusetts Historical Society. Morton, Perez. “An Oration; Delivered at the King’s Chapel in Boston, April 8, 1776, On the Re-Interment of the Remains of the late Most Worshipful Grand-Master Joseph Warren, Esquire; President of the late Congress of this Colony, and Major-General of the Massachusetts Forces; Who was Slain in the Battle of Bunker’s-Hill, June 17, 1775.” https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N11792.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext “Prince Hall”. The Medford Historical Society and Museum. http://www.medfordhistorical.org/medford-history/africa-to-medford/prince-hall/ Register of Marriages at King’s Chapel, Boston. Massachusetts Historical Society. Trumbull, John. “The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 17 June, 1775”. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/34260

1 Comment

12/11/2021 07:17:11 pm

Eventually, through these meetings, Hill met formerly enslaved abolitionist Prince Hall. In 1777, Hall led a group of men in creating a petition to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in response to aspects of the Declaration of Independence they found lacking. Nice post thank you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

King's Chapel History ProgramDive deeper into King's Chapel's 337 year history on the History Program blog. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed